For updated data on hospital-owned specialty pharmacies, see Chapter 3 of DCI's new 2024 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

Click here to see the original post from November 2023.

As many of you know, hospitals and health systems have emerged as significant participants in the specialty pharmacy industry. A new American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) survey provides fresh insights into these specialty pharmacies.

Below, I review key findings on the economics and operations of these specialty pharmacies. I then highlight how hospitals steer prescriptions to their internal specialty pharmacies.

As you’ll see, hospitals use network strategies that would make any pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) proud—especially when combined with the prescribing activities of hospital-employed physicians.

Vertical integration among insurers, PBMs, specialty pharmacies, and providers within U.S. drug channels gets most of the attention. But a parallel vertical integration has been occurring among hospitals, specialty pharmacies, and physicians. Manufacturers and payers must adapt to the growing power and market tactics of hospital-owned specialty pharmacies.

DATA

To profile health systems’ specialty pharmacy strategies, we rely on ASHP Survey of Health-System Specialty Pharmacy Practice: Practice Models, Operations, and Workforce—2022, which was published in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. The full article is free for ASHP members and available for purchase by non-members.

The results are based on nearly 100 health system specialty pharmacies, many of which are substantial businesses. One-quarter of these pharmacies had annual revenues above $100 million for 2022. More than 60% of the pharmacies dispensed more than 15,000 prescriptions annually.

The full peer-reviewed article is filled with useful insights and data. As always, I encourage you to read the complete results. I can only scratch the surface here.

SPECIALTY PHARMACY ECONOMICS

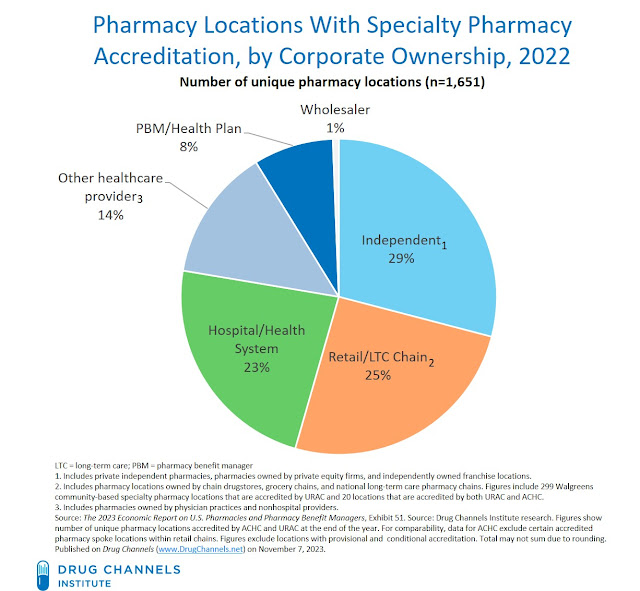

As you can see below, DCI’s data show that hospital-owned pharmacies now account for nearly one-quarter of the 1,651 total accredited specialty pharmacy locations. (For details on specialty pharmacy accreditation, see Section 3.1.3. of our 2023 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.)

[Click to Enlarge]

Consistent with DCI’s figures, more than nine out of ten hospitals in the ASHP survey had accreditation from one or more of the major organizations that help pharmacies develop and verify their capabilities to manufacturers and third-party payers. Most were accredited by one of the two organizations that now dominate accreditation for specialty pharmacies: the Accreditation Commission for Health Care (ACHC) and URAC.

Here are some other fun facts that I gleaned about hospital-owned specialty pharmacies:

- More than one-third rely on an external company for specialty pharmacy services and/or to provide specialty medications. Outside companies are enabling hospitals to reduce the costs and risks associated with launching and operating an in-house specialty pharmacy. The hospitals own these pharmacies, but these private companies earn fees and a share of the profits for managing them. The largest companies that partner with hospitals and health systems for specialty pharmacy services include Shields Health Solutions (now owned by Walgreens Boots Alliance) and Trellis Rx (now owned by CPS Solutions).

- The 340B Drug Pricing Program incentivizes hospitals to operate specialty pharmacies. About 98% of the respondents to the ASHP survey participated in the ever-expanding 340B Drug Pricing Program. Hospitals can generate substantial profits by acquiring discounted specialty drugs and dispensing them from internal pharmacies. What’s more, changes in manufacturers’ 340B contract pharmacy policies have accelerated hospitals’ investments in in-house specialty pharmacy operations.

- Hospitals also rely on 340B contract pharmacies to profit from prescriptions dispensed by external pharmacies in limited networks. Strategies used by payers, PBMs, and manufacturers have narrowed specialty drug channels. This has shifted dispensing to the largest specialty pharmacies owned by vertically integrated organizations. (See DCI’s Top 15 Specialty Pharmacies of 2022: Five Key Trends About Today’s Marketplace.) Most hospitals identified manufacturers’ “refusal to engage” and being “frozen out or blocked by payers” as the biggest barriers to access. (See Table 8 in the full article.)

Consequently, 61% of the 340B-eligible respondents to the ASHP survey contracted with an external pharmacy to provide specialty medications to health-system patients. Most of these hospitals reported using contract pharmacies to dispense medications for which the hospital was excluded from payers’ or manufacturers’ networks. External 340B contract pharmacies often coexist with a hospital’s internal specialty pharmacy.

As we document in For 2023, Five For-Profit Retailers and PBMs Dominate an Evolving 340B Contract Pharmacy Market, the largest five companies—CVS Health, Walgreens, Walmart, Cigna, and UnitedHealth Group—account for three-quarters of total contract pharmacy/covered entity relationships. The superior profitability of a 340B prescription lets hospitals offer generous pharmacy fees and still share a percentage of the prescription savings with the contract pharmacy vendor. Patients, payers, and taxpayers fund these 340B profits.

Self-insured health systems are using a powerful tool to overcome network access barriers: steering prescriptions to in-house specialty pharmacies.

Paralleling the actions of PBMs and payers, a surprising number of self-insured health systems now require their employees—the plan’s beneficiaries—to use the specialty pharmacy that the health system owns and operates. This network design approach ensures that the system’s own pharmacy is part of the limited specialty network, while maximizing usage of an internal specialty pharmacy.

The latest ASHP survey found that 70% of the larger health system specialty pharmacies operate as the exclusive pharmacy within self-insured health systems’ networks. Thus, the hospital’s employees must fill specialty prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy. Others ensure that the health systems’ pharmacy is a preferred option, which means that employees will have lower copays or coinsurance when filling prescriptions at the in-house specialty pharmacy.

[Click to Enlarge]

Although the data are not clearly presented, the ASHP survey seems to indicate that this strategy has been successful. Two-thirds of the largest hospital-owned specialty pharmacies filled 75% or more of the specialty prescriptions dispensed to health-system employees. (See Table 7 in the full article.)

VERTICAL INTEGRATION REDUX

In Section 6.3.1. of DCI’s new 2023-24 Economic Report on Pharmaceutical Wholesalers and Specialty Distributors, we delve into the key factors that have motivated hospital and health system acquisitions of physician practices. We expect the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will provide powerful incentives for further vertical integration, thereby accelerating physician practices’ consolidation into health systems and hospitals.

Vertical integration between hospitals and physician practices enables the type of prescription steering illustrated above. Physicians who are employed by a health system can be mandated or encouraged to send patients to the health system’s in-house specialty pharmacy. For example, the ASHP survey found that 83% of health systems have formal metrics for tracking the prescription capture rate, which measures the number of prescriptions sent to the health system’s specialty pharmacy and/or the number of specialty prescriptions written.

Such vertical integration between hospitals and physician practices can also reduce network access barriers. For example:

- A hospital could direct its employed physicians not to prescribe a new specialty drug unless the manufacturer adds the hospital’s specialty pharmacy to its network.

- Hospital-employed physicians can demand that the hospital’s pharmacy gain access to a manufacturer’s limited dispensing network.

- A hospital could demand that a payer include its in-house pharmacy as a preferred network option as part of its overall contracting.

The battle for the specialty patient still has much to teach us all.

No comments:

Post a Comment