The GoodRx situation highlights crucial issues about the complex web of relationships and conflicts that support today’s discount card model. Below, I break down the economics of the discount card business to help frame the outlook for discount cards.

As I explain, discount cards are really just another form of spread pricing. As the market for patient-paid prescriptions has expanded, disputes about the appropriate split of these spreads will pressure pharmacy-PBM relationships and drive change in the discount card business model.

A well-known African proverb states: “When elephants fight, it's the grass that suffers.” Will investors continue to support GoodRx—or move on to greener pastures? Read on and see what you think.

READ ME

Here are the relevant materials from GoodRx’s 2022:Q1 earnings announcement: As always, I encourage you to review the original source material for yourself.

You may find it useful to review my previous articles about GoodRx and its business model: I place GoodRx within the broader context of patient-paid prescriptions in Section 4.3. of DCI’s 2022 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

TUSK TO TUSK

GoodRx described the unexpected financial surprise in its letter to shareholders:

“In addition, we recognized that a grocery chain had taken actions late in the first quarter of 2022 that impacted acceptance of discounted pricing for a subset of drugs from PBMs, who are our customers, and whose pricing we promote on our platform.”On its earnings call, GoodRx disclosed that the chain accounted for less than 5% of the pharmacies in its retail network, but “almost one-quarter of its prescription transaction revenue.” That equates to about $38 million in GoodRx’s first quarter revenues, or about $150 million annually. The company projected that the financial impact would be roughly $30 million in the second quarter, but wouldn’t forecast beyond that point.

This was a startling disclosure. Like many other people, I was not aware that GoodRx had become so dependent on a single chain. Since the announcement, the company’s already depressed stock price has remained below $9. In early 2021, its stock price peaked at nearly $57. Ouch.

According to Wall Street analysts, the grocery chain that no longer accepts the GoodRx discount card for some or all prescriptions is Kroger. Multiple consumer posts on Twitter have confirmed this awkward reality. (For example, see here and here.)

We estimate that Kroger accounts for only 3% of total U.S prescription revenues. This suggests that GoodRx was dramatically over-indexed to a single chain.

As you can read in the earnings call transcript, GoodRx management tried valiantly to spin this situation. They correctly noted that the dispute is not between GoodRx and Kroger, but instead between Kroger and at least one of the PBMs that manages GoodRx’s retail discounts.

That’s why the GoodRx team made an analogy to the Walgreens/Express Scripts dispute from 2012. (They didn’t explicitly mention these two companies, but it’s clear from the context.) Travel back 10 years via the Drug Channels wayback machine for a refresher: Walgreens is Losing Its Battle with Express Scripts and Walgreen Cuts a Deal with Express Scripts.

I found GoodRx’s commentary to be confusing and hard to decipher. Here’s my take on what’s really going on.

DISCOUNT CARDS = SPREAD PRICING

Spread pricing is one way that third-party payers can compensate a PBM for plan administration and other services. With spread pricing, a payer compensates a PBM by permitting the PBM to retain differences, or spreads, between (a) the amount a PBM charges the payer, and (b) the amount the PBM pays the pharmacy that’s dispensing the prescription to a patient. We estimate that spread pricing has become much less important to large PBMs’ overall profitability. (See Section 11.2.3. of our 2022 pharmacy/PBM report.)

However, many people don’t appreciate that spread pricing is the primary way that PBMs profit from discount cards. Consequently, the Kroger/PBM dispute is really a fight over how this spread gets split.

The chart below illustrates the flow of products and money when a patient uses a discount card to pay the full cost of their generic drug prescription, without using third-party insurance. Since generic drug manufacturers don’t pay rebates to PBMs or payers, those flows have been eliminated from the chart.

[Click to Enlarge]

There are some notable differences from the conventional scenario illustrated in our well-known follow-the-dollar chart:

- When using a discount card, the patient is the payer. There is no third-party payment for the prescription. The patient’s out-of-pocket payment comprises the pharmacy’s entire payment for the prescription. (More on this issue below.) In the chart above, the contractual and financial flows between PBMs and third-party payers have been removed.

- The PBM collects a per-prescription fee from the pharmacy whenever a patient uses a discount card program. The pharmacy’s net reimbursement equals the patient’s prescription payment minus the discount card fee. Thus, this fee reflects a spread over the net reimbursement that the pharmacy earns. Like many other payers, patients generally don’t know that a PBM collects this fee.

- The PBM doesn’t keep the entire discount card spread. The PBM shares a portion of this fee with the discount card vendor that directed the patient to the pharmacy. The PBM will pay the discount card vendor a percentage of its fee or a fixed per-prescription amount. Regardless of the form, GoodRx reports that it earns about 15% of the patient’s total retail prescription cost. See my commentary in this post from last August.

Let’s assume that GoodRx keeps 75% of discount card spread, while PBMs keep the remaining 25%. Here are some rough estimates of the GoodRx/PBM/Kroger prescription economics:

- Total prescription revenue from consumers using GoodRx at Kroger pharmacies = $1 billion (= $150 million ÷ 15%)

- GoodRx transaction revenue from Kroger = $150 million

- PBM transaction revenue from GoodRx at Kroger = $50 million (assuming 25% of total discount card spread)

- Net Kroger prescription revenues = $800 million (= $1 billion minus $200 million discount card spread)

TRAMPLED UNDER FOOT?

The figures above are becoming crucial in understanding the forces driving the future of discount cards. Here are three trends to watch:

1) Patient-paid prescriptions are growing.

Prescription costs are increasingly shifted to patients through deductibles and coinsurance. Consequently, a growing share of prescriptions have no third-party contribution, because patients pay the full cost out of pocket.

What’s more, generic prescription pricing is so broken that more than 70% of the consumers who used GoodRx already had commercial or Medicare insurance. GoodRx has even estimated that more than half of prescriptions filled using its discount card were cheaper than the average commercial insurance copays for the 100 most purchased medications.

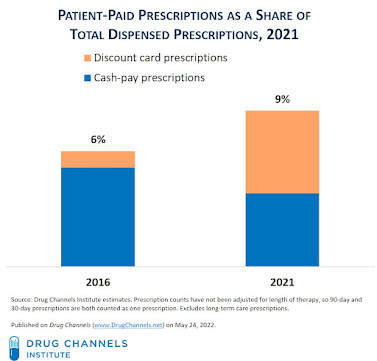

We estimate that patient-paid prescription accounted for about 9% of unadjusted prescriptions in 2021. Discount cards were more than half of this patient-paid prescription activity.

Patient-paid prescriptions that use a discount card are not considered cash-pay, because the claims are adjudicated by a PBM. Thus, they lead to a consumerization of retail prescriptions—but not necessarily of the pharmacy and PBM industries.

What’s more, generic prescription pricing is so broken that more than 70% of the consumers who used GoodRx already had commercial or Medicare insurance. GoodRx has even estimated that more than half of prescriptions filled using its discount card were cheaper than the average commercial insurance copays for the 100 most purchased medications.

We estimate that patient-paid prescription accounted for about 9% of unadjusted prescriptions in 2021. Discount cards were more than half of this patient-paid prescription activity.

[Click to Enlarge]

Patient-paid prescriptions that use a discount card are not considered cash-pay, because the claims are adjudicated by a PBM. Thus, they lead to a consumerization of retail prescriptions—but not necessarily of the pharmacy and PBM industries.

2) Pharmacies will push back against shrinking discount card margins.

When a patient uses a discount card, the pharmacy must pay a fee for dispensing to a patient who may have been willing to pay the same prescription price directly to the pharmacy anyway. However, our wacky drug channel effectively prevents pharmacies from offering low cash prices that match the discount cards.

PBMs have been trying to expand these spreads, in part because discount card vendors are demanding ever-higher payment rates. Consequently, pharmacy margins for discount card prescriptions are being squeezed. This adds one more profit pressure to the long list of negative headwinds facing retail pharmacy.

Pharmacies will have a tough time recapturing these margins. Most areas of the U.S. have an oversupply of retail pharmacy locations.

PBMs have been trying to expand these spreads, in part because discount card vendors are demanding ever-higher payment rates. Consequently, pharmacy margins for discount card prescriptions are being squeezed. This adds one more profit pressure to the long list of negative headwinds facing retail pharmacy.

Pharmacies will have a tough time recapturing these margins. Most areas of the U.S. have an oversupply of retail pharmacy locations.

3) PBMs will react to the danger from discount cards.

I have long postulated that discount cards could be the true disrupter that upends PBMs’ pharmacy benefit economics, plan sponsors’ decisions, and the entire generic market. Generic drugs account for nearly 90% of a PBM’s claims processing activity. Discount cards are incentivizing people to bypass their own insurance plans and access the network rates of another PBM—or even their own plan’s PBM disguised as a discount card.

PBMs have profited from discount cards’ rapid growth. I think they now recognize the dangers of this growth for the value of their benefit management services. Keep an eye on the following strategies:

In my recent video webinar PBM Industry Update: Trends, Controversies, and Outlook, I explained how patient-paid prescriptions could disrupt the PBM business.

PBMs have profited from discount cards’ rapid growth. I think they now recognize the dangers of this growth for the value of their benefit management services. Keep an eye on the following strategies:

- PBMs are trying to increase discount cards spreads and/or retain a greater a portion of these spreads. So far, discount card vendors have been able to sustain their margins by working with smaller and hungrier PBMs that want to build their volume. For instance, GoodRx’s share of revenue from its three largest PBMs has been dropping, from 61% in 2018 to 34% in 2021. This suggests that the company is going deeper into the market to maintain competition.

- PBMs are trying to insert some sort of “discount card” pricing into commercial benefit plans. Both Express Scripts and Prime Therapeutics have announced such programs. As I argued in a previous article, PBMs can hide behind discount cards to undermine the network rates offered to their own clients. I still have trouble understanding the circumstances in which a member’s out-of-pocket cost under a PBM-managed benefit plan would be higher than their cost using a discount card program operated by the same PBM.

Let’s see if GoodRx will be savvy enough to avoid becoming trampled grass.

No comments:

Post a Comment