For proof, look at GoodRx’s 2020 financial results for its discount card business. The company accounted for an estimated $3.4 billion in U.S. prescription revenues—and earned nearly $500 million in fees from PBMs.

Incredibly, three out of four consumers who used GoodRx already had commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid insurance. This means that someone—the consumer, their employer, and/or the government—paid insurance premiums for a pharmacy benefit managed by a PBM. Yet it was still worthwhile for people to bypass their plan’s out-of-pocket costs and PBM network rates in favor of a different PBM’s rates. As I explain below, such arbitrage creates potent conflicts between PBMs and their plan sponsor clients.

Don’t blame GoodRx for this mess. I give it credit for helping consumers navigate a crazy system that incentivizes people to bypass their own insurance plans. But it’s hard not to dislike a system that enables these games. Read on and let me know what you think.

READ ME

Here are the relevant materials from GoodRx’s most recent earnings announcement:

As always, I encourage you to review the original source material for yourself.

CASHING IN ON COMPLEXITY

I outlined GoodRx’s profit model in How GoodRx Profits from Our Broken Pharmacy Pricing System.

Briefly, discount cards such as GoodRx save consumers money by leveraging the craziness baked into the U.S. pharmacy pricing, reimbursement, and dispensing system.

A consumer who uses a discount card benefits by gaining access to a PBM’s network rate. The discount card passes a portion of rebates and network discounts directly to patients at the point of sale. Patients therefore avoid paying a retail pharmacy’s far higher usual and customary (U&C) retail cash price for their prescriptions.

For a deep dive into the economics of patient-paid prescriptions, see Section 4.3. of our new 2021 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

FOLLOW THE DOLLARS

The prescriptions available via GoodRx (or any other discount card) are not considered cash-pay, because the claims are adjudicated by a PBM. The PBM collects a per-prescription fee from the pharmacy whenever a consumer uses a discount program there. The PBM shares a portion of this fee with the discount card vendor that directed the patient to the pharmacy.

For 2020, Navitus (owned by SSM Health and Costco), MedImpact, and Express Scripts (owned by Cigna) accounted for 42% of GoodRx’s revenues.

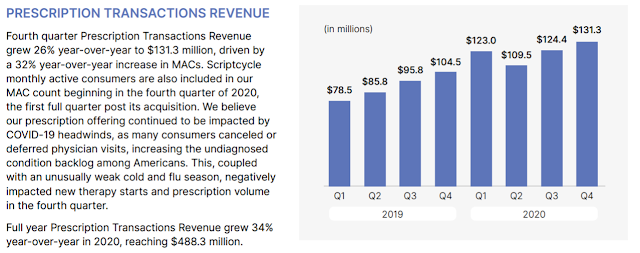

In its fourth quarter earnings report, GoodRx summarized the money that PBMs collectively paid it:

Wow. In 2020, GoodRx collected an incredible $488.3 million in fees, up by 34% from the 2019 figure.

GoodRx has disclosed that its prescription fees average about 14.4% of the retail prescription price. This implies that GoodRx accounted for about $3.4 billion in prescription dispensing revenues. That’s nearly 1% of the total U.S. market

Incredible.

FIND THE DOLLARS

You may be surprised to learn that patients with insurance are GoodRx’s biggest users.

Per the GoodRx investor deck, 70% of its consumers already have commercial or Medicare Part D insurance.

That’s because benefit designs and network rates can differ among PBMs. This difference creates an opportunity for the patient to reduce out-of-pocket expenses by accessing the rates of another PBM.

For instance, a patient’s copayment could be higher than another PBM’s cash price. Or a high-deductible health plan could make patients pay the full negotiated rate between a pharmacy and PBM. (See Exhibit 172 in our new pharmacy/PBM report.) However, a different PBM’s negotiated rate could be lower than the rate available from the PBM of the patient’s primary insurance.

There’s another twist to this scheme. GoodRx cleverly makes PBMs compete for patients who are already being serviced by another PBM. This can provide a subtle but significant benefit to the PBM, which may profit by peeling a patient away from a sophisticated plan sponsor.

CASHING IN ON COMPLEXITY

I outlined GoodRx’s profit model in How GoodRx Profits from Our Broken Pharmacy Pricing System.

Briefly, discount cards such as GoodRx save consumers money by leveraging the craziness baked into the U.S. pharmacy pricing, reimbursement, and dispensing system.

A consumer who uses a discount card benefits by gaining access to a PBM’s network rate. The discount card passes a portion of rebates and network discounts directly to patients at the point of sale. Patients therefore avoid paying a retail pharmacy’s far higher usual and customary (U&C) retail cash price for their prescriptions.

For a deep dive into the economics of patient-paid prescriptions, see Section 4.3. of our new 2021 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

FOLLOW THE DOLLARS

The prescriptions available via GoodRx (or any other discount card) are not considered cash-pay, because the claims are adjudicated by a PBM. The PBM collects a per-prescription fee from the pharmacy whenever a consumer uses a discount program there. The PBM shares a portion of this fee with the discount card vendor that directed the patient to the pharmacy.

For 2020, Navitus (owned by SSM Health and Costco), MedImpact, and Express Scripts (owned by Cigna) accounted for 42% of GoodRx’s revenues.

In its fourth quarter earnings report, GoodRx summarized the money that PBMs collectively paid it:

[Click to Enlarge]

Wow. In 2020, GoodRx collected an incredible $488.3 million in fees, up by 34% from the 2019 figure.

GoodRx has disclosed that its prescription fees average about 14.4% of the retail prescription price. This implies that GoodRx accounted for about $3.4 billion in prescription dispensing revenues. That’s nearly 1% of the total U.S. market

Incredible.

FIND THE DOLLARS

You may be surprised to learn that patients with insurance are GoodRx’s biggest users.

Per the GoodRx investor deck, 70% of its consumers already have commercial or Medicare Part D insurance.

[Click to Enlarge]

That’s because benefit designs and network rates can differ among PBMs. This difference creates an opportunity for the patient to reduce out-of-pocket expenses by accessing the rates of another PBM.

For instance, a patient’s copayment could be higher than another PBM’s cash price. Or a high-deductible health plan could make patients pay the full negotiated rate between a pharmacy and PBM. (See Exhibit 172 in our new pharmacy/PBM report.) However, a different PBM’s negotiated rate could be lower than the rate available from the PBM of the patient’s primary insurance.

There’s another twist to this scheme. GoodRx cleverly makes PBMs compete for patients who are already being serviced by another PBM. This can provide a subtle but significant benefit to the PBM, which may profit by peeling a patient away from a sophisticated plan sponsor.

For example, most plan sponsors require PBMs to pass through most or all of manufacturer rebates on brand-name drugs. What happens to the rebate when there is no plan sponsor demanding the rebate funds? Or when a PBM has no AWP discount rate guarantees to meet?

I wonder how many plan sponsors have delved into the potential conflicts when their PBM also operates a thriving discount card business.

HATING THE GAME

For now, GoodRx is benefiting consumers. And its model suggests a pathway by which the PBM business could be truly disrupted for traditional, non-specialty drugs.

Alas, I’m still troubled by the complex web of relationships and conflicts that have created this market opportunity for GoodRx and its peers. GoodRx co-founder Doug Hirsh once said: “A company like ours should not have to exist.”

He’s not wrong.

I wonder how many plan sponsors have delved into the potential conflicts when their PBM also operates a thriving discount card business.

HATING THE GAME

For now, GoodRx is benefiting consumers. And its model suggests a pathway by which the PBM business could be truly disrupted for traditional, non-specialty drugs.

Alas, I’m still troubled by the complex web of relationships and conflicts that have created this market opportunity for GoodRx and its peers. GoodRx co-founder Doug Hirsh once said: “A company like ours should not have to exist.”

He’s not wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment